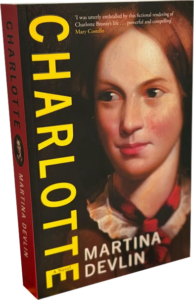

Creative Learnings – Martina Devlin

Novelist & Journalist

Charlotte is my fourth historical fiction novel. My fifth tilt at the historical fiction genre, if you include my collection of short stories, Truth & Dare, about women who shaped Ireland.

Avoid falling down a rabbit hole

It’s hard not to fall down a rabbit hole when you begin. It’s quite addictive because the research is compelling. You have to avoid researching endlessly.

At some stage you just have to hit the pause button and start writing and tell yourself that if there’s a gap in your knowledge – if there’s something you don’t fully understand as you’re writing the book – you can go back and do more research.

Challenge yourself

To push myself and my literary practice I told the story of Charlotte (about the Jane Eyre novelist Charlotte Brontë) in reverse chronology. It would have been easier to tell it in forward chronology but I up-ended my narrative.

In the edit stages I had to be very very careful about the placement of information because of that reverse chronology framework. I wrote it forward and then turned it on its head.

I challenged myself deliberately. I don’t think I would have been able to go with this reverse chronology process earlier in my career. It took a lot of concentration at the writing stage and attention to detail during edits.

Find an editor who can push you

I worked with a different editor this time for Charlotte but he’s from the same publishing team I cooperate with at The Lilliput Press. I would like to work with him again because I felt that we pulled well together. His name is Seán Farrell and I specifically asked for him. I had worked with him on a short story for a collection put out by the same publisher and I was very impressed by his edit notes and the way he nudged me to go the extra mile. His first book comes out in February, Frogs for Watchdogs.

There are many good editors in the industry but find one who’s on your wavelength and who can help you bring your book to the next level, or even just push you and say, “You need to give more thought to this character or this narrative trajectory,” for example. Somebody who’ll make you work a bit harder. It’s great to experience that.

It’s always worth doing another edit

I’ve learned that it’s always worth doing another edit. I’ve always known in principle the first draft isn’t where it’s at; you just have to do multiple drafts. But sometimes it’s tempting to let a piece of work go before you should.

With Charlotte I kept doing another draft and then another draft. I could see that it improved the work.

You do have to meet the publishing industry’s deadlines but it is always worth taking the time to do one more edit of the work. Or if deadlines are against you, edit a section that’s perhaps niggling at you; go over that again. That’s a lesson I’ve learned which the work benefits from.

Combine working with a publicist and doing your own publicity

The publisher for Charlotte has an in-house publicist but they also used a very good external publicist, Peter O’Connell, and I was very happy with his contribution. He did a good job of putting Charlotte on people’s radar. Afterwards, when there was a lull in publicity, I asked myself, “Where are the gaps?” I thought that we could do some specific publicity in the North of Ireland because there is a strong northern element to the story I’ve written in Charlotte.

I made a few calls and sent a few emails myself and I’m doing events in the North now. Overall, it’s been a combination of working with a publicist who knows what they’re doing and me doing some of my own.

There are a lot of books out there – it’s a crowded marketplace – so writers do have to be proactive.

Visit places

I’m a great believer in material culture and I find objects very useful to help revivify people who actually lived. I just find that they somehow inspire me. I also feel it is very important to visit places and walk around where my characters (who were also real people) lived. If I can see the landscape and buildings they would have seen, it feeds my imagination.

I loved wandering around the Brontë Parsonage Museum. I remember the bannisters there and running my hand down them, thinking all of the Brontës would have touched this and now I am. It gave me goosebumps. The past feels very near at times like that.

I particularly noticed that the windows had deep window seats and I had this strong mental picture of those three little girls and their brother curling up on them with their books and sketchpads.

There’s no substitute for research

I particularly get comfort from feeling I understand a period and its political and social climate reasonably well. There’s no substitute for research. I’m always mystified when I hear other writers – I’m thinking of several famous, successful authors here – say, “Oh, I pay someone else to do my research”. I think, “How can you outsource that?”, because you never know what you’ll find when you begin delving and it sometimes sends you in another direction from where you intended. It allows you, for example, to platform new characters or give a greater emphasis to certain characters than you intended at the outset.

As I was researching Charlotte, I discovered important Brontë memorabilia, including personal possessions, had lain for decades undiscovered in a house in Banagher in Co. Offaly: first editions, annotated manuscripts, a portrait of the sisters, their gowns, bonnets, sewing boxes, portable writing desks… Much of that memorabilia is now in the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth, Yorkshire and people can go and see it. In its way, it can help to keep those genius sisters and their work alive.

The dilemma for me was how could I combine all this memorabilia (which had been in the care of Charlotte’s widower and his second wife), with the story of Charlotte in Ireland? How did her Irish identity – for which I’m making the case in the novel – feed into her writing and how did it influence her work? Marrying these two elements was quite a challenge but very enjoyable for me.

If I hadn’t done all the research I did; if I hadn’t come across this treasure trove of memorabilia in Banagher, I might have told the novel through the voice of Charlotte. But the objects’ existence, and their significance in the Brontë story, persuaded me to use Mary Anna Bell Nicholls’ voice, the second wife of Charlotte’s widower, Arthur Bell Nicholls. It was a way of coming at the narrative slantways, while emphasizing what a central role she had in the story I wanted to tell.

I began by re-reading the primary sources – meaning all seven Brontë novels. Although my novel is about Charlotte, it mattered to me to read Emily’s novel and Anne’s two novels, and their poetry, because her sisters were so important to her.

I read multiple biographies about Charlotte, but also about Arthur Bell Nicholls and Patrick, her father. There weren’t any biographies that I came across of Mary but in a way that was useful to me; it freed me to imagine her. I’m interested in women who would not be remembered by history but for their connection – which turns out to have significance because of some part they play – with a better–known individual.

Consider subject matter that appeals to people beyond yourself

Writing is a creative undertaking, and tapping into the imagination is hugely important. However, if we want to get published, we have to be aware that publishing is an industry. Sometimes you need to ask yourself, “Will this subject matter appeal to readers and a publisher? Is working on this project the best use of my time? I want to get published, I want a book at the end of this process. Will the idea I am currently trying to pin down as a story deliver that goal? Is there another story I could tell with a stronger chance of being published?”

Think hard about the book you are trying to write. It doesn’t have to be a blockbuster, or reinvent the wheel, or win prizes, but it must attract readers other than yourself and your circle of friends.

Good writing and storytelling are a lot tougher than it looks. But getting published, ending up with your name on the jacket of a book, seeing it in shops and libraries, is enormously satisfying. It feeds something within us.

With Charlotte I was specifically looking for interesting women because that’s what fascinates me, but I also wanted these exceptional women to resonate with readers.

I was conscious there is already a big audience for work about the Brontës because they have captured the public imagination. At events, you don’t have to explain who Charlotte Brontë is. She is an easier sell than some potential subjects.

Charlotte has been fairly straightforward to publicise because the story behind the novel is easy for both media and the public to get their heads around: the Brontës have a strong Irish connection which hasn’t been explored sufficiently. I find that when I talk about it, people are fascinated by these Irish elements because the Brontës are seen as jewels in the English literary canon and quintessentially Yorkshire writers who were inspired by the moors.

Patrick Brontë, father of Charlotte, was an Irishman. Brontë is a gentrified version of Brunty or Prunty from the Irish name Ó Proinntigh. Charlotte married an Irishman and they honeymooned in Ireland. She sent letters back to England talking about what she saw in Ireland. As soon as you explain this, it becomes a story that’s very easy to talk about as inspiration for a novel. That Irish connection has been the easiest part of working on Charlotte.

All things being equal, I knew that if I could write a decent novel about the Brontës, emphasizing the Irish backstory, then it was something with potential to land with the public. For me, it was a way of retelling a story we thought we know already, and giving it added value.

If you’d like specific career advice relating to your creative field, we run free workshops as well as mentorships rounds.

mindingcreativeminds.ie/mentorship-programme

mindingcreativeminds.ie/events